👋 Hey {{first name | reader…}} it’s Jamie!

In this edition of ⚗️ DistillED, we’re focusing on worked examples—used well, they reduce cognitive load and help focus students’ cognitive processes effectively.

📊 Quick Poll!

Before we jump in, I’d love to know about your use of worked examples in your own classroom. Your response helps shape future editions of ⚗️DistillED.

Which part of the worked-example sequence do you find hardest to get right?

What are Worked Examples?

A worked example is a step-by-step demonstration of how to solve a problem or complete a task, with the thinking made visible along the way. Rather than asking students to immediately “have a go”, it’s about explicitly doing the following:

Modelling the learning process step by step by writing it out clearly.

Explaining the decisions that drive each step through deliberate think-alouds.

Showing what expert performance actually looks like in real time.

Involving students so thinking stays active through prediction, questioning etc.

John Sweller, whose work underpins Cognitive Load Theory, observed that novices learn very differently from experts. Experts see underlying structure and patterns; novices don’t — yet. When novices are asked to solve problems too early, they rely on trial-and-error or guesswork, which overloads working memory and blocks learning. This is why Sweller argued that instruction must first supply the schemas novices lack, rather than expecting them to discover those schemas independently.

“Worked examples can efficiently provide us with the problem solving schemas that need to be stored in long-term memory.”

Essentially, worked examples are about:

Reducing Cognitive Load: Freeing up working memory so students can focus on understanding the method, not struggling to work out the process.

Learning Underlying Ideas: Making the structure, steps, and decisions visible so students can recognise and apply the method independently later.

Preventing the Practice of Errors: Avoiding early trial-and-error that embeds misconceptions before students know what “right” looks like.

Building Fluency Before Independence: Creating confidence and accuracy through guided success before responsibility is released.

In fact, worked examples are most powerful early in learning, when content is new and schemas are still forming. At this stage, students benefit from seeing every step modelled clearly.

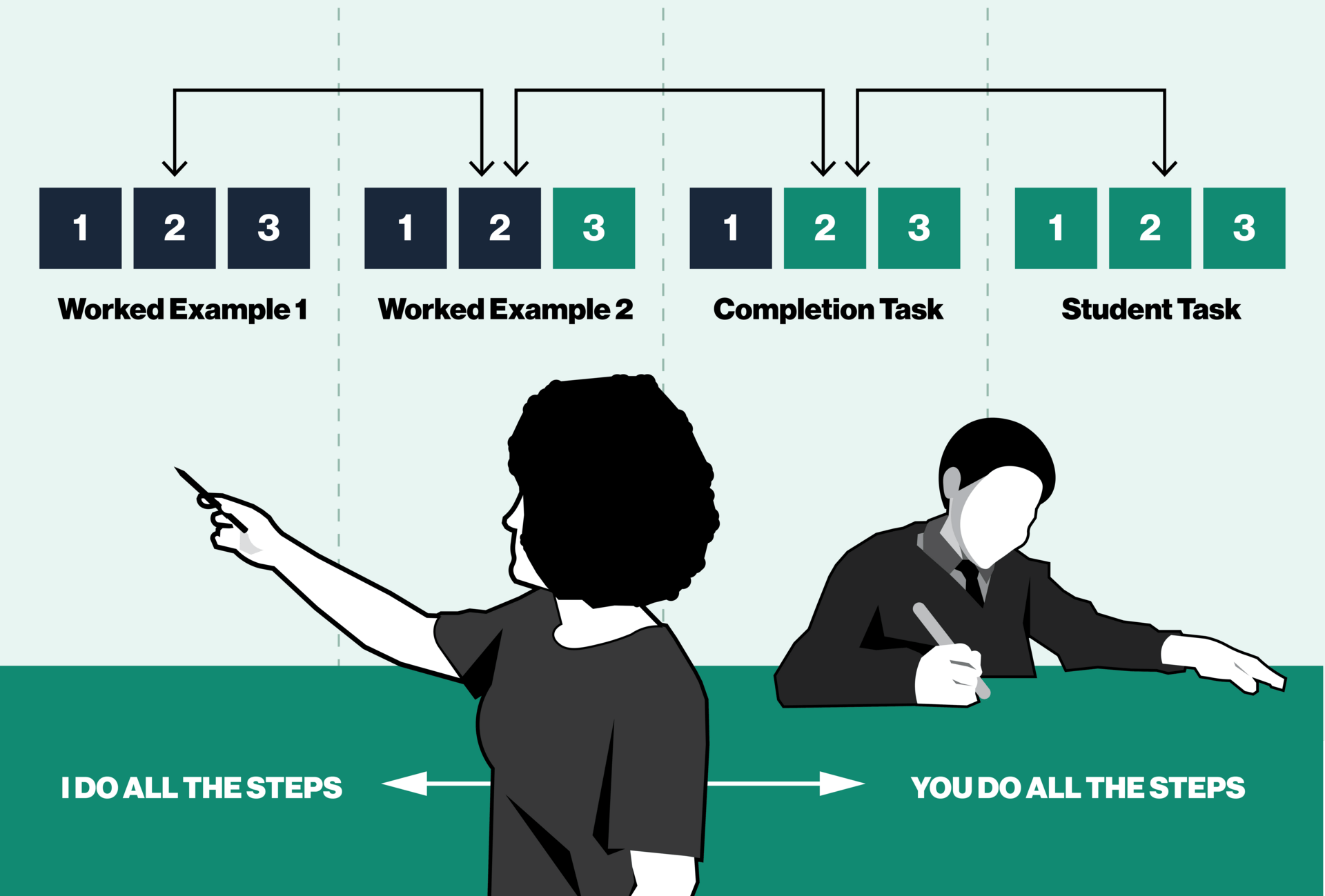

The graphic below visualises how responsibility gradually shifts from teacher to student. It begins with fully worked examples, where the teacher completes all steps and makes the thinking explicit. It then moves to partially worked (or completion tasks), where some steps are provided and students supply the rest. Finally, students transition to independent tasks, where they complete all steps on their own.

Over time, the sequence moves deliberately from “I do all the steps” to “You do all the steps” — reducing cognitive load early, then fading support as fluency and confidence grow.

The research is remarkably consistent on worked examples… Let’s take a look.

Why do Worked Examples Matter?

Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory shows that working memory is limited. When students are asked to solve unfamiliar problems, much of their mental effort is spent on searching for a solution rather than learning how the solution works. As Sweller famously argued:

“Solving a problem and acquiring schemas may require largely unrelated cognitive processes.”

Translation! Getting an answer isn’t the same as learning. Trial-and-error problem solving can look productive, but for novices it often overloads working memory and leaves little capacity for building durable understanding.

This is why worked examples are so powerful. By showing students how a problem is solved — step by step — they remove the need for inefficient search and direct attention to the underlying structure of the task. As Kirschner, Sweller & Clark (2006) explain, worked examples reduce unnecessary cognitive load and allow students to focus on forming schemas that can be stored in long-term memory.

“Studying a worked example both reduces working memory load because search is reduced or eliminated and directs attention to the essential relations between problem-solving moves.”

Ultimately, worked examples matter because they protect limited working memory and accelerate schema formation, setting students up for success when independence is eventually required.

Research on the worked example effect consistently shows several benefits:

Higher Success Rates During Early Learning: Students are far more likely to experience accurate, successful practice — a key condition for confidence and motivation.

Faster and More Secure Schema Development: Students grasp the structure and method of a task more quickly, enabling better transfer to new but related problems.

Better long-term performance than problem solving alone: Students who study worked examples often outperform peers who were asked to solve problems from the outset, even on later independent tasks.

In short, worked examples don’t lower the bar (it’s not spoon feeding). They build the cognitive foundations that make independent thinking possible.

Keep reading to find out HOW and discover helpful resources…